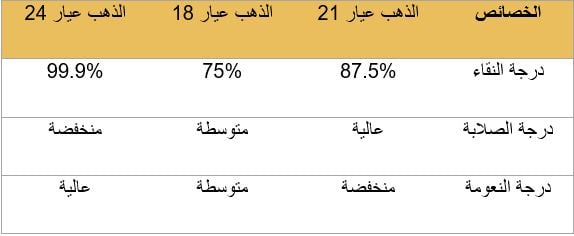

BTC - إزاي تعرف عيار الذهب بسهولة؟ عن طريق الدمغة التي يختم بها الذهب، فعيار (24) يحمل الرقم 999.9 أو 995 أو 24، وعيار (21) يحمل الرقم 875 أو رقم 21. #استثمر_في_الذهب #

ماهو الفرق بين عيارات الذهب 24 و 21 و 18 - متجر نكلس لبيع الذهب والمجوهرات من قلائد اساور سبائك ذهب وأكثر